Natural sweetening with allulose

What can this rare sugar do that other alternative sweeteners can’t?

Photo © Shutterstock.com/Oleksandra Naumenko

In a market abundant with natural sweetening options, allulose is primed to carve out a hefty market share. This so-called rare sugar is reportedly 70% as sweet as table sugar but with 90% fewer calories and many of the same functional qualities.

But why is it called a rare sugar?

Allulose gets its classification because, despite being present in numerous foods (corn, figs, raisins, jack fruit, and more), it’s found in these foods only in very small amounts. Through enzymatic processes, ingredient suppliers are able to extract significant amounts of allulose from large quantities of plant material. That’s why corn ends up being the preferred plant source for most industrial allulose production worldwide. According to Ingredion Inc. (Westchester, IL), which markets Astraea allulose from corn, sourcing the ingredient from other plants just isn’t economically feasible.

Beyond the simple economics, numerous other factors make allulose a sweetener worth considering for beverages, dairy, baked goods, confectionery, and other food products. We highlight some of them here.

Photo © AdobeStock.com/gamjai

No Blood Sugar Spikes

Once consumed, allulose is reportedly absorbed but not significantly metabolized. In other words, the sweetener shouldn’t have the same effect as table sugar on blood sugar levels. This potential benefit makes allulose an attractive sweetener for consumers who choose to avoid sugar, such as diabetics. It’s an attractive feature of some other alternative sweeteners, too.

Allulose suppliers are quick to confirm this lack of a postprandial glucose response, and a number of peer-reviewed studies support their theory. Still, it’s worth noting that a few recently published studies warn of a lack of long-term data on this relatively new commercial ingredient.1–2

References

- Noronha JC et al. “The effect of small doses of fructose and allulose on postprandial glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, acute feeding, equivalence trial.” Diabetes, Obesity, & Metabolism, vol. 20, no. 10 (October 2018): 2361–2370

- Braunstein CR et al. “A double-blind, randomized controlled, acute feeding equivalence trial of small, catalytic doses of fructose and allulose on postprandial blood glucose metabolism in health participants: the Fructose and Allulose Catalytic Effects (FACE) Trial.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 6 (June 9, 2018)

Photo © Shutterstock.com/wustrow

Functional Benefits of Sugar

Where allulose separates itself from other alternative sweeteners is in its functional likeness to table sugar. It has the same bulking abilities of sugar and the same browning properties. Allulose is also highly soluble in beverages and not quick to crystallize in high-solid systems. Erythritol, for example, is an alternative sweetener missing several of these characteristics.

Allulose also happens to be particularly useful in frozen food products, such as ice cream, because of its freeze point depression. “For freezing point depression in frozen food products, allulose delivers excellent handling in manufacturing, storage stability, and desirable texture and other sensory characteristics,” says Abigail Storms, vice president of sweetener platform and global platform marketing for Tate & Lyle PLC (London), which markets Dolcia Prima allulose.

Photo © iStockphoto.com/Maksud_kr

Blends

Where many alternative sweeteners are sweeter than sucrose, allulose is less sweet. It’s reportedly 70% as sweet as sucrose, despite providing a similar sweetness onset and linger.

By blending allulose with more high-intensity sweeteners, such as stevia, manufacturers can enhance the sweetness of food products without compromising on allulose’s useful functionality. Keeping this in mind, Icon Foods (Portland, OR) markets Ketosweet allulose and Ketosweet+ blends of allulose combined with stevia and/or monk fruit.

“Buyers sourcing from us get the benefit of savings on logistics since one compound is coming from one location rather than multiple sources,” says Thom King, Icon Foods president and CEO. “Additionally, natural high-intensity sweeteners can be very unforgiving if over-dosed into process. Our blend is consistent each and every time.”

Photo © AdobeStock.com/meenkulathiamma

Safety

If the utility of allulose hereto shared is enough to peak your interest in purchasing allulose, consider, too, the safety work that’s been conducted on allulose. A recent study of gastrointestinal tolerance suggests acceptable ranges of use for public safety,3 and suppliers should also be able to help you determine how much allulose to use in your products safely and effectively.

Though research is shedding light on alternative sweeteners that may, when compared to regular sugar, have favorable effects such as on body weight and metabolism, limiting consumption of any sweetener is a good rule of thumb that both manufacturers and consumers should keep in mind.

References

3. Han Y et al. “Gastrointestinal tolerance of D-allulose in healthy and young adults: a non-randomized controlled trial.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 12 (December 19, 2018): E2010

Photo © iStockphoto.com/duckycards

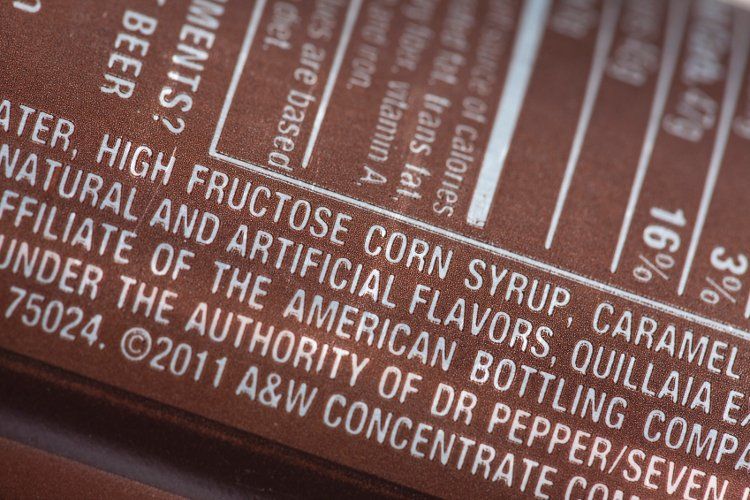

Labeling

Until recently in the United States, manufacturers of products containing allulose had to label the ingredient as an “added sugar” on FDA’s Nutrition Facts panel, a requirement that irks some industry members. Since allulose contains so few calories and doesn’t appear to raise blood sugar once ingested, interested members would prefer it if the ingredient wasn’t treated in the same way as sugar. Labeling allulose as “added sugar” can create misperceptions for shoppers, including those for which allulose is most targeted: people with diabetes and those who otherwise want to avoid sugar. In 2015, Tate & Lyle submitted a citizen’s petition to exclude allulose from this mandatory labeling.

Years later, FDA has answered. This April, FDA issued draft guidance indicating that the agency intends to exercise enforcement discretion to allow allulose to be excluded from the total and added-sugar declarations on the Nutrition Facts and Supplement Facts labels.

Susan Mayne, PhD, director of FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, acknowledged the different properties ascribed to allulose: “The latest data suggests that allulose is different from other sugars in that it is not metabolized by the human body in the same way as table sugar,” she said in a statement. “It has fewer calories, produces only negligible increases in blood glucose or insulin levels, and does not promote dental decay.”

As reported in April by Nutritional Outlook’s associate editor, Sebastian Krawiec, according to FDA’s draft guidance: “Allulose will continue to count toward the caloric value of food on the label and must still be declared on the ingredients list. According to Mayne, this is the first time FDA has stated its intent to allow a sugar to not be included as part of the total or added-sugars declaration on labels. The guidance document also states the FDA will exercise enforcement discretion to allow manufacturers to use 0.4 calories per gram of allulose when calculating the calories from allulose in a serving, in contrast to the 2016 Nutrition Facts label rule, which stated that allulose must be counted as four calories per gram of sweetener.

Both Ingredion and Tate & Lyle celebrated the news in statements.

Afrouz Naeini, Ingredion’s regional platform leader for sugar reduction in the U.S. and Canada, said in an April 18 press release: “Construction is well underway at Ingredion’s dedicated Astraea allulose manufacturing site in Mexico and commercial scale availability of products are expected this year. With the FDA announcement, we can now partner more closely with customers as they look to harness the full potential of Astraea allulose and help them bring winning products to market that meet consumers’ taste and indulgent wants and health and wellness needs.”

In an April 17 press release, Abigail Storms, vice president of global strategic marketing at Tate & Lyle, said, “Leading the commercialization of allulose back in 2015 with Dolcia Prima allulose gave us the opportunity to be the first to work with food and beverage manufacturers on their calorie reduction challenges using this ingredient. We’ve seen incredible solutions, but the labeling was a challenging hurdle until now. I am excited at the impact we can now make together with our customers on the reduction in sugar consumption in brands across categories in the U.S. This is a breakthrough in our ability to offer consumer and customer relevant solutions in the face of today’s obesity and diabetes health crises.”

Robby Gardner is a food and agriculture specialist living in Los Angeles. Visit www.robbygardner.com.

Prinova acquires Aplinova to further increase its footprint in Latin America

April 7th 2025Prinova has recently announced the acquisition of Brazilian ingredients distributor Aplinova, which is a provider of specialty ingredients for a range of market segments that include food, beverage, supplements, and personal care.