Beauty Supplements

The notion that what you eat contributes to the way you look is nothing new. Recently, however, there has been renewed appreciation for "beauty from within"-the idea that a healthy diet and lifestyle contribute to the appearance of skin, hair, nails, and teeth. Consuming sufficient amounts of vitamins, minerals, and other bioactive ingredients has an effect on outward appearance. As the baby boomer generation ages and longs to maintain its youthful glow, the category of dietary supplements for beauty will continue to grow.

What concerns me, though, despite my agreement with the mantra that beauty comes from within, is the catchy-and sometimes questionable-marketing associated with the intersection of products that promote beauty (cosmetics) and ones that are ingested for nutrition and wellness (dietary supplements).

Legally, there is no such thing as a cosmeceutical, or a cosme-supplement, or a nutri-cosmetic. Marketers have come up with all kinds of catchy names to describe this category of products. However, the reality is that FDA doesn't recognize any of these hybrids as valid regulatory categories.

Nonetheless, consumers are increasingly demanding these products, leaving product formulators, marketing executives, and regulatory personnel to navigate the requirements and restrictions for these products. Assumptions about permissible ingredients and legitimate advertising claims can be different between these categories, so experienced cosmetic companies that venture into the uncharted world of dietary supplements do so at their own peril.

It's All in the Definition

While there may be no agreed upon definition of what constitutes beauty, from FDA's perspective, a product is one thing or another, or perhaps both-but there is no in between.

According to the Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act (FD&CA), the term cosmetic means "articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body or any part thereof for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance," as well as articles intended for use as a component of these items.

By contrast, the term dietary supplement means "a product intended to supplement the diet that bears or contains one or more of the following dietary ingredients: a vitamin; a mineral; an herb or other botanical; an amino acid; a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake;" or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combination of any ingredient described above. The law also provides that a dietary supplement means a product that is intended for ingestion in a tablet, capsule, powder, softgel, gelcap, or liquid form. It is not represented as conventional food or for use as a sole item of a meal or of the diet.

Consider also that a drug is defined as "an article intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals; or an article (other than food) that is intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals..."

Step One: Figure Out What You Are

The first hurdle for manufacturers is to determine whether the product they are making is a cosmetic, a supplement, or a drug-because FDA treats them as very different things. And that comes down to three questions.

First, how is the product to be used/absorbed/ingested?

A cosmetic must be "applied to the body," while a dietary supplement must be "ingested." Patches, creams, and lotions, no matter how many vitamins are included in them, cannot be dietary supplements because they are not ingested. Even a product that dissolves under the tongue is not considered a dietary supplement because FDA states that sublingual absorption is not ingestion. And yet, there are any number of topically applied products that mistakenly put a "Supplement Facts" box on their labels and call themselves a dietary supplement in error.

Second, what are the ingredients?

A cosmetic may contain virtually any ingredient, as long as it has been determined to be safe when used as directed. By contrast, a dietary supplement must be composed of one or more permissible dietary ingredients (a vitamin, mineral, herb or other botanical, amino acid, or other dietary substance) and also inactive components such as excipients (binders, fillers, etc....).

Unless a manufacturer is prepared to submit a new dietary ingredient notification (NDI) to support the reasonable expectation of safety of an ingredient, all ingredients must have already been on the market as a dietary supplement prior to 1994. (The mere presence of a given ingredient in the food supply prior to 1994 does not constitute a "grandfathered" ingredient.) Any other ingredients for an ingested product could be deemed a drug by the agency. Don't assume that just because you can swallow a product, it qualifies as a supplement. In fact, some substances, like anabolic steroids, are drugs simply because of their identity.

Also, consider that a beauty drink could be a food as well. FDA has opined that beverages of 8 oz or more are really not supplementing the diet, but rather, are a part of the diet. Thus, this delivery form is most likely a conventional food, not a dietary supplement. So, a drink packed full of vitamins and nutrients that is supposed to reduce wrinkles and improve skin elasticity may be neither a cosmetic nor a dietary supplement. It may be a food, and the ingredients may instead be subject to the generally recognized as safe (GRAS) standard, which is different than the NDI review process for dietary supplements.

The same could be true of beauty snacks that might make claims that the ingredients promote smoother, more-supple skin, or shinier hair. If the item is ingestible, doesn't make drug claims, and would actually constitute an item of the diet (like a nutrition bar or a cookie), then it's probably food.

Third, what is the intended effect for which the product is being marketed?

The definitions of cosmetics, dietary supplements, and drugs all rely, at least in part, on the intended use as illustrated by the marketer. So, products that claim to treat acne, or to cure psoriasis or prevent dandruff, are all going to be considered a drug, no matter what ingredients the manufacturer might use, or the delivery form (cream, liquid, or pill).

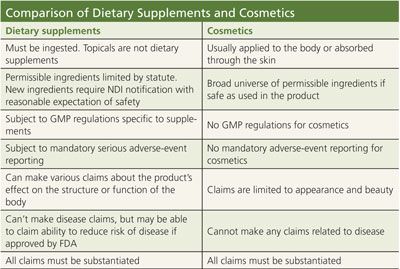

The implications of this determination are, if you'll pardon the pun, more than cosmetic. Dietary supplements, as well as drugs, are subject to mandatory reporting of serious adverse events. Cosmetics are not. Both dietary supplements and drugs have their own sets of Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations specific to those products. Cosmetics do not. Dietary supplements require structure/function claims submitted to FDA within 30 days of their introduction-not for FDA's premarket approval, but as notice to the agency. If a dietary supplement goes beyond a structure/function claim and wants to promote its ability to reduce the risk of disease, even a disease that's related to appearance, those claims are subject to tighter regulation as health claims, and the manufacturer must seek FDA approval prior to using these claims.

Drugs, of course, must go through the entire new drug approval process, which includes careful examination of their claims by FDA. In contrast, cosmetics have a fairly easy go of it with respect to their appearance or beautification claims, as long as they don't stray beyond the bounds of cosmetic claims.

Step Two: Although the Voice of Beauty May Speak Softly, the Voice of Regulation Does Not

It's been said that the voice of beauty speaks softly. While beauty may speak softly, when it comes to advertising regulations, the voice of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is loud and clear. When it comes to advertising, cosmetics and supplements are subject to the same requirements that FTC imposes on all consumer advertising. Whatever the claims may be-whether express or implied-they must be truthful, not misleading, and substantiated by competent and reliable scientific evidence.

The FTC has developed an extensive set of guidelines for marketers of dietary supplements for what it considers appropriate substantiation, or support, for these claims. Even cosme-supplements, as marketers might call them, are subject to the FTC's advertising guidelines.

Perhaps good evidence of the popularity of cosme-supplements is the fact that even the National Advertising Division (NAD) of the Council of Better Business Bureau is examining more ads involving these products. In the past year, NAD has conducted three reviews of these beauty-enhancing supplements. Marketers contemplating a new product that claims beauty-enhancing effects from a supplement would be wise to review these decisions for boundaries on acceptable claims. (For more information, visit www.bbb.org/us/us/national-advertising-division.)

The first advertising review involved a product called Biosil, a supplement containing collagen, keratin, and elastin. The ad made claims such as "reduces fine lines and wrinkles by 19%," "clinically proven to give a more youthful look," "creates thicker, stronger hair," and "provides stronger, more-break-resistant nails."

NAD's review was particularly critical of the numerical claim ("reduces wrinkles by 19%") and the "clinically proven" claim. Other claims in the ad were deemed to satisfy the thresholds for substantiation because the marketer did its homework first. The advertiser had relied on well-conducted studies that indeed demonstrated reductions in maximum roughness of the skin and increase viscoelasticity. Other studies, again using oral ingestion of the ingredients in amounts similar to those found in the product, resulted in statistically significant improvements to hair, skin, and nails.

The second review examined a supplement called Dermasilk Anti-Wrinkle containing Vitamin E, astaxanthin, carnosine, benfotiamine, and GliSODin. The ads tout the product as "a revolutionary, age-defying, antiwrinkle supplement," "clinically proven to help reduce the appearance of wrinkles and fine lines in just two weeks," and "helps increase firmness, hydration, elasticity, and density." In this case, the marketer had been less thorough.

NAD noted that it is risky to assume that bioactive compounds that work topically will have a similar effect in an oral supplement. Can they survive the trip through the digestive tract intact and cross the intestinal barrier to be delivered to the skin? This is an inferential leap that supplement formulators should not assume, so studies of dermally applied ingredients may not support a supplement claim.

In vitro studies, or even animal studies, without evidence that the ingredient works identically in the human body, may also trip up the cosme-supplement marketer. Differences in dosage between the relied-on study and the product in question pose additional problems for supporting the veracity of the advertising claims. NAD even recommended discontinuing the claim "like getting a facelift without the invasive surgery," noting that in the context of the other claims, such a statement would be viewed by consumers as more than mere puffery.

The third case involved advertising for a supplement called Cellulase Gold that was making claims such as "94% reported seeing results," "clinically proven to actually help reduce cellulite by helping promote healthy cell metabolism," "you could see firmer, smoother, better-looking skin," and "may lead to measurable reduction in your hips, thighs, abdomen, and ankles."

NAD found the claims were well supported by a published, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical study-the gold standard of research-that used the product itself in the study. Although NAD agreed that most of the claims were well substantiated, it raised its eyebrows over the use of before/after photos in the ads because photos do not represent results that a consumer can reasonably expect. It also frowned on the claim that the supplement "can produce results without any changes in diet, exercise, or lifestyle."

Marketing Pitfalls: More Than Skin Deep

In short, product developers and marketers must be wary of formulating cosmetic ingredients into dietary supplements. Beauty may be more than skin deep, but so are the pitfalls for one who doesn't understand the difference in regulations among these products or appreciate the demarcations between cosmetics, dietary supplements, and drugs.

As the evidence grows that healthy diets and good nutrition contribute to outward appearances, so too will consumer demand for these products. But only careful navigation of FDA and FTC regulations and understanding of how to translate the research into defensible advertising claims will create a thing of beauty under the law.

HHS announces restructuring plans to consolidate divisions and downsize workforce

Published: March 27th 2025 | Updated: March 27th 2025According to the announcement, the restructuring will save taxpayers $1.8 billion per year by reducing the workforce by 10,000 full-time employees and consolidating the department’s 28 divisions into 15 new divisions.